The parties to a charterparty may also agree that certain matters or details will be determined by one of the parties to the putative contract or their agents, or by a third party (such as a bank), upon a formal declaration or nomination. In such cases, upon the declaration or nomination being made (e.g. the identity of the vessel to be chartered, the identity of the port of loading or discharge, or the quantity or nature of the cargo to be carried), the declaration or nomination is written into the contract. Where such nominations are required, the party making the nomination is under an obligation to make that nomination; it is not a mere liberty. There is probably an implied obligation to make a declaration or nomination with which it is possible to comply.[1]

Likewise, specific places of loading and discharge may be designated in the contract or may remain to be nominated by the charterer from a range of possible places or within stated geographical limits, the subsequently nominated places again being irrevocably incorporated into the definition of the contractual adventure. Accordingly, as a matter of law, those ports were “written into” the charterparty as if they had been named at the time of contracting. Once so written into the charter the charterers had no right to nominate a different discharge port. The authorities was summarized by Judge Diamond QC:[2]

In the absence of any special provision in a charter-party, the effect of the nomination of a loading or discharging port by the charterer is that the charter-party must thereafter be treated as if the nominated port had originally been written into the charter-party and that the charterer has neither the right nor the obligation to change that nomination.

As indicated above, a nomination of a loading or discharge port or place may be made by naming it in the charter itself, or subsequently, pursuant to an obligation on the charterer to make the nomination. In either case, in the absence of some special provision, a valid nomination once made completes the definition of the parties’ contractual obligation and is accordingly irrevocable.[3]

In The Shelley[4], Devlin J. observed[5]:

It is clearly settled by the authorities that where there is an express reservation in the charter-party to the charterer to nominate the port or berth, that port or berth, when nominated, is to be treated as if it had been written into the charter-party. I have not been troubled in detail with the authorities that may cover the position where the right to nominate is implied rather than expressed, but Mr. Roskill has very properly conceded that there can be no difference, as logically clearly there cannot. That being so, the position seems to me to be that when the charterers nominated New Hibernia Wharf, it was to be treated as if it was written into the charter-party as the place of discharge, and it follows from that that it cannot be altered by the charterers. To permit the charterers to alter it would be to permit a unilateral alteration of the contract.

In The Vancouver Strike cases[6], Sellers L.J. ruled[7]:

The result, in my judgment, is that, on these charter-parties, the nomination of Vancouver was a proper nomination and the charter-parties were to be treated as if Vancouver were the sole port available in the written contract, all the others being treated as struck out; that the charter-parties were to be read as if wheat in bulk were the sole commodity to be loaded and carried from Vancouver, as no option was exercised by the charterers and there was no obligation on them to exercise an option; that once Vancouver had been, as it was, properly nominated there was no right or duty on the charterers to change it and therefore Clause 31 can properly be invoked and the lay days did not count during any time when the loading was delayed by the strike.

And in The Prometheus[8], Mocatta J. said[9]:

This was a port charter and the charterers had the implied right (and indeed obligation) to name a berth or actual loading spot, not by reason of any express words of the charter, but under the decision in The Felix, (1868) L.R. 2 Ad. & Ecc. 273. This was a right of selection and not election, as would have been the case under a "berth" charter; i.e., one expressly giving the charterers the right to order the actual loading berth or spot. In such a charter the berth or spot ultimately ordered by the charterers has to be treated as if originally written into the charter. See Tapscott v. Balfour, (1872) L.R. 8 C.P. 46, at p. 52; Tharsis Sulphur and Copper Company, Limited v. Morel Brothers & Co., [1891] 2 Q.B. 647, and Reardon Smith Line Ltd. v. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, [1962] 1 Q.B. 42, at pp. 90, 91 and 115; [1961] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 385, at pp. 408, 409 and 421. Accordingly, the charterers, although they had, naturally enough, intended the Prometheus to load ex a grain elevator at a berth in the New Docks and had made all necessary arrangements to this end, could not rely upon cl. 30 if all such berths were occupied until 05 10 hours on Monday, May 31, unless they could establish that it was beyond their control to have loaded at least some of the cargo at another available berth in port during the time the vessel was kept waiting for a berth in the New Docks to become available.

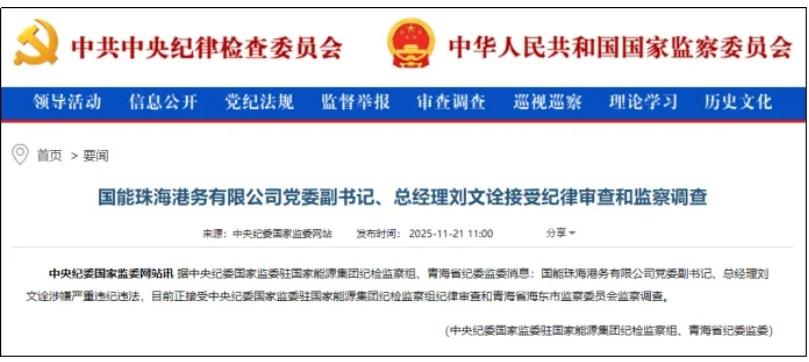

Recently, in London Arbitration 1/24, in the tribunal’s view, the charterers validly declared Zhoushan and Taixing as the discharge ports on 20 June. The effect of doing so was to treat those two ports as if written into the charterparty from the outset.

No doubt recognising this, the charterers sought to rely on arguments of variation, estoppel and waiver. The difficulty for them with each of these contentions was that it was clear from the exchanges between the parties at the time that the owners were at all times expressly insisting that the charterers had no right to nominate Tianjin and that the owners would only proceed there under protest, reserving all rights to receive the freight payable on the nomination of Zhoushan and Taixing and without waiving their rights to such freight. This was confirmed in the terms of the escrow agreement eventually concluded. This was fatal to all of the charterers’ submissions.

The fact that the voyage for which the additional freight was claimed was never performed did not give rise to any unjust enrichment of the owners at the expense of the charterers. The freight was paid at the contractual rate for the contractually nominated voyage. Freight was deemed earned on shipment discountless and non-returnable. That was a complete answer to the charterers’ submission of a total failure of consideration.

The tribunal found that the owners were entitled to the freight payable on the nomination of Zhoushan and Taixing as held in the escrow account.

[1] Carver on Charterparties, 2nd ed, Sweet & Maxwell, at para.2-029.

[2] The Jasmine B [1992] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 39 at p.42.

[3] Voyage Charters, 5th ed, Informa law, at para.5.20.

[4] The Shelley (1949) 83 Ll.L.Rep.137.

[5] Ibid, per Devlin J. (as he then was) at p.139.

[6] The Vancouver Strike cases [1961] 1 Lloyd’s Rep.385 (C.A.).

[7] Ibid, per Sellers L.J. at p.411.

[8] The Prometheus [1974] 1 Lloyd’s Rep.350.

[9] Ibid, per per Mocatta J. at p.353.

海运圈聚焦专栏作者Alex (微信公众号 航运佬)

2024-01-29

2024-01-29 807

807