一、Description on delivery

- NYPE 1946 lines 9 –10

- “... and capable of steaming, fully laden, under good weather conditions about ... knots on a consumption of about ... tons of … best grade fuel oil ...”

- NYPE 1993 lines 18-20

- ...

- Speed about ... knots, fully laden, in good weather conditions up to and including maximum Force ... on the Beaufort wind scale, on a consumption of about ... tons of ...

- BALTIME 1939

- PART I Box 12

- Speed capability in knots (abt.) on a consumption in tons (abt.) of m …

- PART II lines 10-13

- ... and fully loaded capable of steaming about the number of knots indicated in Box 12 in good weather and smooth water on a consumption of about the number of tons fuel oil stated in Box 12 ...

- The above are examples of contractual undertakings that the chartered ship is capable of a certain speed under a certain consumption in the conditions specified. As intermediate terms, they represent a promise that the detail is accurate. A material mis-description will entitle charterers to damages for losses suffered as a consequence of a breach.

- See Brian Williamson, a leading London arbitrator, in his article 《UNDERSTANDING PERFORMANCE CLAIMS 》.

- It is generally accepted that a ship must comply with her description on the date the charter is made, although in The Apollonius Mocatta, J. said that, except in the case of Class, the ship must accord with its description at the time of delivery. In The Didymi, Bingham L.J. said that the description of the ship’s speed and consumption contained in the pre-amble (to the charterparty) “refers to the vessel’s capacity at the date of the charterparty”. In The Al Bida Evans J. and Parker L.J. seemed to have assumed that Mocatta J’s approach (with respect to speed and consumption) was correct. Irrespective of whether the ship’s described speed and consumption attaches at the time of contract or on delivery, such a warranty does not represent a continuing obligation. Charterers must therefore rely on further undertakings if performance is expected to apply for the duration of the charter period.

- We have carefully considered the parties’ arguments and the authorities relied on. The position was by no means clear. However, it appears that, where a vessel is fixed on terms which include lines 9-10 of the NYPE judicial opinion is divided as to whether the speed and consumption figures constitute as at (i) the date of the fixture or (ii) the delivery of the vessel into the charterparty.

- The charterparty in question in this case did not contain lines 9-10 because they had been expressly deleted and replaced by clause 29. That clause is headed “Vessel’s Description” and sets out the vessel’s capabilities. It does not include any words such as “throughout the currency of this charterparty” or “during the currency of this charterparty” which would have suggested that the vessel’s description as set out in the clause was to be maintained throughtout the charterparty period.

- See The “Hebei Rainbow”, London Arbitration (2005) 681 LMLN 2(2)

- In the light of the above we have concluded that there was no continuing warranty as to the vessel’s performance contained in the charterparty. The Charterers did not advance any alternative case on the failure to maintain and therefore their claim for under-performance/over-consumption does not succeed. Moreover, it follows that the Owners are entitled to be paid by the Charterers the sum of usd191,452.34 that has (in the light of our findings) been wrongfully deducted. We have awarded interest at a commercial rate on that sum from the customary one month after redelivery. In line with the ususal rule that costs follow the event, we have awarded the Owners their costs, together with the costs of our Award. We have reserved jurisdiction to deal with the quantum of the costs in the event they cannot be agreed.

- See The “Hebei Rainbow” and The “Matrix” case.

- See The “Gas Enterprise”[1993] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.352, Where clause 5 provides:

- …undertake so to maintain the vessel during the period of service under this Charter…

- Owners undertake that:

- …The maximum average speed of the vessel during the period of this Charter shall be…

- Held, by C.A. (Lloyd, Butler-Sloss and Roch, L.JJ.) that (1) sub-cl. (4) provided a contractual yardstick for measuring the extent of the vessel's capacity to perform and there was no reason for confining the application of the yardstick to periods when the weather was force 4 or less; the warranty set out in sub-cll. (1)-(3) was expressed to apply generally in respect of all voyages whether laden or in ballast and prima facie the charterers were entitled to be compensated for any breach of that warranty.

- Charterers nowadays routinely use services such as WNI or AWT to provide routing advice to Masters to avoid the worst of expected bad weather. However, it became common for the Master to report the vessel’s noon position, and bunkers consumed in the preceding day. From this the routing firms decided to provide an additional added-value service of analysing the vessel’s speed and performance against warranty. However they did not originally extrapolate from good weather days, but instead provided an overall voyage calculation in which the speed was adjusted by a detailed but completely unexplained “weather effect” and “current effect”. These were routinely disregarded by arbitrators precisely because they were unexplained, although the vessel’s log reports and the routing services’ estimates of the daily weather were compared. Generally the log books would be preferred if the results were not wildly different as the Master was the man on the spot, but resort might be had to other independent sources if there were unexplainable differences, even if these could never solve the uncertainties of current and possible localised weather effects.

- No doubt the routing services’ analysis is becoming more sophisticated, and the presentation of their evidence now accords with the favoured approach of the arbitrators. However, mere assertion still does not qualify as evidence. For example it is not clear whether the weather reported on a particular day comes from a report from a vessel half a mile away from the subject vessel, or just from satellite analysis. I for one do not know how the effect of current is calculated, and I believe a claim put forward only on the basis of the unexplained analysis of one of these services cannot found a claim, without independent support, unless the arbitrator is directed by a clause in the charterparty to rely upon it.

- See London Shipping Law Center (LSLC) in their《Speed and Consumption Issues》.

- If there is any wording such as “Report from Weather bureau will be Final and Binding”, the result maybe different.

- The statutory formula are:

- Propeller Slip =(Engine distance – ship distance)/ Engine distance x 100

- If divided by 24 ( basis daily 24 hrs),

- Propeller slip = ( Engine distance/24- ship distance/24) / Engine distance/24 x 100, Then will be:

- Propeller slip = ( Engine speed- ship speed) / Engine speed x 100

- Ex. if vessel’s speed is 12knots, distance run 288nms, the slip is 5%, therefore, the vessel’s engine speed will be 12.63knots=288/(1-5%)x24.

- Slip will be affected by below:

- Draft , Trim, Propeller pitch (for ships with controllable pitch propellers (CPP) ,Current/Swell, Weather-induced ship motions , Rudder-induced ship motions ,Operating transients (rapid power and speed changes) ,Hull and propeller fouling etc

- Constant, but high, slip figures are indicative of hull fouling.

- High, but variable, slip figures are indicative of current/swell.

- See Brian Williamson in 《understanding performance claims》:

- Factors that affect hull resistance and propeller performance are inter-dependent. Wake, the body of water which trails behind the ship, is caused by skin friction and has a velocity relative to the ship. Propeller pitch is the distance a propeller would advance if turned through one complete revolution in a solid medium. Theoretical advance assumes 100% efficiency. The difference between theoretical and actual is known as the slip and is expressed as a percentage of theoretical value. Apparent slip, a function of propeller pitch, engine RPM and speed through undisturbed water, is calculated by comparing distance run through the water and propeller distance. The daily routine of calculating slip based on navigational data uses distance over the ground. Such result will be affected by current, so can be negative if a strong favourable current is encountered.

- 18. When the objective is to establish whether or not a ship is capable of her warranted speed and/or consumption, a detailed inspection of both deck and engine logs ought to provide a clear indication. If designed trial speed and RPM on a vessel with a fixed bladed propeller in the laden condition are known, apparent slip will provide an indication as to whether progress through the water has been retarded by internal and/or external factors. Current apart, any variation in slip is symptomatic of a change in the relationship between propulsive power and speed. Constant, but high, slip figures are indicative of hull fouling. High, but variable, slip figures are indicative of hull fouling and current.

- West Of England , 《Defence Guides-Speed and consumption claims》:

- Further, high “slip” figures in the main engine log can also indicate adverse tides and/or currents. (Slip is the difference between the theoretical distance the propeller should have moved (pitch multiplied by revolutions made) compared to the actual distance achieved over the ground for the same time period).This is not always the method used by the weather routing companies, who often calculate an average speed which includes those days where the weather conditions were not “good”.

- A weather factor is then applied to the overall calculation to estimate the extent to which the vessel’s speed was affected by the conditions apparently encountered.

- Speed and consumption basis good weather condition of upto Beaufort force 4 and Douglas sea state 3 on about 12(L)/13 (B) knots on about 33mt(L) /32mt(B) per day +0.1mt MDO…

- Speed and consumption basis good weather condition of upto ①Beaufort force 4 and② Douglas sea state 3 and③ no adverse current and ④no negative influence of swell on about 12(L)/13 (B) knots on about 33mt(L)/32mt(B) per day +0.1mt MDO

- No continuously warranty, no wordings such as “throughout the currency of this charterparty” or “during the currency of this charterparty” or “apply to all voyages” etc.

- The principle feature of a continuing warranty is that it should establish the benchmark against which owners’ continuing obligations are to be measured. The choice of words used will determine the warranty conditions that apply. In the above example, the warranty conditions are as follows:

- (a) In weather conditions not exceeding Beaufort force 4

- (b) In sea conditions not exceeding Douglas sea state 3

- (c) No adverse current

- (d) No negative influence of swell

- When all four conditions exist, the ship will be expected to demonstrate an ability to perform at the promised speed and consumption and will only be excused from doing so if one or more of the warranty conditions is/are absent. Periods of warranty conditions are loosely referred to by experts as good weather days, simply because they are used to working from log abstracts. They are more accurately described as good weather periods, as the periods of interest are not restricted to full days only.

- Two fundamental considerations must be addressed in establishing sampling periods of warranty conditions for analysis.

- Firstly, (a) how long should the good weather periods identified continue uninterrupted, and secondly

- (b) what minimum period should exist overall on a cumulative basis on any single voyage?

- As the analyst is obliged to work with the tools provided, there can be no standard test for carrying out an evaluation. From the gathered sampling, a subjective test will take into account all of the following:

- (a) The overall duration of the voyage.

- (b) The overall distance covered.

- (c) The variety of weather and sea conditions encountered.

- (d) The distances run in each period of warranty conditions.

- (e) The number and frequency of periods when warranty conditions prevailed.

- (f) The slip recorded on a daily basis and the voyage overall.

- (g) The relevant engine data provided.

- It is suggested, however, that this approach - assessing breach only by reference to performance in good weather – may owe more to pragmatism than principle. As weather data and performance modelling become more sophisticated and accurate, it may become possible for experts to undertake a single, reliable analysis, comparing the performance in fact achieved in the conditions in fact experienced against the performance that ought to have been achieved by a ship capable of the promised performance. Such an analysis would, in effect, both test for breach and assess the measure of the breach if there has been one.

- See 7th Edition 《Time Charters》 Chapter 3-The Ship, 3.68.

- If warranty conditions do not exist at any time, or for sufficient uninterrupted periods, or there is an insufficient cumulative period, a thorny issue is whether any assessment of the ship’s capabilities at all can be made.

- The strict legal approach is one of construction. If a contract provides that a ship is capable of performing at a certain speed and a certain consumption under stated wind and sea conditions, how can it be possible for a breach to be proven in circumstances where the contractual provisions do not apply?

- In other words, if charterers are only entitled to view performance when warranty conditions exist, if such conditions never existed, there can be no benchmark against which to measure performance.

- In the court’s judgment, the tribunal erred in law when it directed itself that an admissible period of good weather had to be a period of 24 consecutive hours running from noon to noon. The charterparty merely referred to “good weather”. There were no words in the charterparty which justified construing good weather as meaning good weather days of 24 hours from noon to noon.

- Accordingly, the appeal would be allowed. The award would be remitted to the tribunal to determine whether the two periods of good weather in the first leg of the ballast voyage (14 and 16 hours) were by themselves or cumulatively a sufficient sample to enable a breach to be established. They could not be excluded from consideration on the grounds that each was less than 24 hours. If they were a sufficient sample then the arbitrator had to determine whether they established a breach of the performance warranty and, if they did, apply that breach to the whole of the charterparty, excluding any periods of slow steaming on the instructions of the charterers, in order to quantify the charterers’ claim for damages.

- See London Arbitration (2015) 940 LMLN 1. if as Owners, suggest to add “day means continuously 24 hours from noon to noon.”

- See London Arbitration (2015) 940 LMLN 1. if as Owners, suggest to add “day means continuously 24 hours from noon to noon.”

- In my judgment Miss Paruk has correctly identified an error of law by the arbitrator when he directed himself that an admissible period of good weather must be a period of 24 consecutive hours running from noon to noon. The charterparty merely referred to "good weather". There are no words in the charterparty which justify construing good weather as meaning good weather days of 24 hours from noon to noon.

- I therefore consider that the appeal should be allowed. The award should be remitted to the arbitrator for him to determine whether the two periods of good weather in the first leg of the ballast voyage (14 and 16 hours) are by themselves or cumulatively a sufficient sample to enable a breach to be established. They cannot be excluded from consideration on the grounds that each is less than 24 hours. If they are a sufficient sample then the arbitrator must determine whether they establish a breach of the performance warranty and, if they do, apply that breach to the whole of the charterparty, excluding any periods of slow steaming on the instructions of the charterers, in order to quantify the charterers' claim for damages.

- See The “Ocean Virgo” [2015] EWHC 3405, Where Teare J. said at p18 and p20.

- (b) Distance steamed

- There was a further discrepancy between the two sides relating to the overall distance steamed. The owners had said that because of very bad weather and sea conditions, the vessel was obliged to tack, which increased her distance steamed from 5,046.9 to 5,224.6 miles. AWT assessed mileage as 5,049.3 miles.

- Held, that the tribunal would give the Owners the benefit of the doubt in that regard.

- See London Arbitration 15/05 (2005) 670 LMLN 1

- It’s suggest that distance to run to be calculated basis sea buoy to sea buoy.

- At the risk of stating the obvious, manoeuvring in confined spaces or in heavy traffic ought conventionally to be excluded from any calculations.

- See London Shipping Law Center (LSLC) in their circulates:《Speed and Consumption Issues》.

- If as Owners, suggest to instruct the Master to report the charterers’ weather bureau once the vessel commence manoeuring, especially in confined spaces, such as transit Malacca Strait or shallow water or fishing area or any other heavy traffic area etc.

- See London Arbitration 21/18 (2018)1013 LMLN 1, where Tribunal held: The vessel’s speed had intentionally been reduced on approach to Port Said, as would be the case for all commercial vessels, due to heavy traffic, separation schemes and safety reasons. Using the correct time, until 14.35, produced a revised average speed for the day of 13.57 knots, well within the warranted speed.

- In my judgment, the owners’ construction is correct, and is justified in law by the principle or rule that a contracting party is not to be held liable in damages for failing to achieve more than the minimum obligation which he undertook by his contract. The construction of the words is plain enough: ‘about’ clearly does import some margin below, and if relevant, above, the stated figure of 15.5 knots. When it is sought to hold the shipowner liable in damages for breach of this undertaking, he is entitled to have his liability measured by reference to the lower end of the range.

- See The Al Bida [1986] 1 Lloyd’s Rep.142 per Evans J at p146.

- With regard to the extent of the allowance to be given for the tem “about”, although on some occasions in the past, arbitration tribunals had referred to allowances of less than 5% on bunker consumption, the current practice was almost invariably to apply an allowance of 5% unless there were special circumstances. There was no reason to depart from that practice in the present case.

- See London Arbitration 15/05 (2005)670 LMLN 1 and London Arbitration 20/07 (2007)723 LMLN 3.

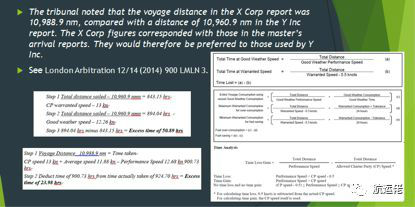

- Also see Arbitration 12/14 (2014)900 LMLN 3 :

- As regards the overconsumption claim, Y Inc had concluded that the vessel overconsumed 71 mt of bunkers. X Corp had concluded that the vessel did not overconsume at all. There were two reasons for the difference. In the first place, Y Inc made no allowance for the “about” factor of (as was common ground) 5 per cent.

- In The Al Bida [1987] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 124 (C.A.), Parker, L.J. said, “The margin imported in the word ‘about’ cannot be fixed as a matter of law. The margin must, as the arbitrators have rightly held, ‘be tailored to the ship’s configuration, size, draft and trim etc.’.”

- In considering capability, Parker L.J. said that it was not surprising that both speed and consumption were expressed as averages as about. The averages, in his view, did no more than recognise that both normal working conditions and moderate weather may so vary that, from day to day, the consumption and speed may (indeed inevitably will) move either side of the specified figures, and that the only fair thing to do is to take a running average over a reasonable period. The method is not a matter of law and is a matter for the arbitrators to assess. What was a matter of law was that the pre-amble did not require an actual average to be taken over the period of the charter, or indeed any period.

- See London Arbitration 21/18 (2018)1013 LMLN 1 , clause of 29. Vessel’s description, where provides:

- SPEED AND CONSUMPTION: BALLAST: ABT 14K ON ABT 26T IFO 380 NDAS ABT 13K ON ABT 23T IFO 380 NDAS LADEN: ABT 14K ON ABT 29T IFO 380 MDAS ABT 13K ON ABT 26T IFO 380 NDAS ABOVE SPEED AND CONSUMPTION WARRANTIES ALWAYS UP TO BEAUFORT SCALE FORCE 4/DOUGLAS SEA STATE 3 AND WITH A TOLERANCE OF 5PCT ABOUT. NO NEGATIVE INFLUENCE OF CURRENTS/SWELL.

- The tribunal held that: The charterers’ suggestion that the words “A TOLERANCE” were in the singular and so applied only to one of the two allowances ignored the preceding reference in the same sentence to both the speed and consumption warranties. The words therefore applied to both. Thus the speed and consumption warranties were both subject to an allowance of 5 per cent for the term “ABT”. If the tolerance was indeed intended to refer to only one of the speed or consumption figures warranted it was far from clear which of the figures it would refer to and how it would to be applied.

- …That correlation for an all-waves average of 1.25m was a significant wave height of just under 2m. If they used a significant wave height of 2m to judge fair weather days, they were in full compliance with the original meaning of Douglas sea state 3…

- See London Arbitration 12/14 (2014)900 LMLN 3

- It’s suggested that significant wave height less than 2M will be qualified as good weather day.

- The significant wave including wind wave and swell wave, calculated and formulated: significant wave height² =wind wave height² + swell wave height² .

- If as Owners, Suggest to remark: Douglas sea state 3 means significant wave height less than 1.25m.

- In assessing the days of good weather, the tribunal stated the following:

- On the previous day, when swell of 2 metres height was recorded, the average speed was shown as being 10 knots, and on the day before that in similar conditions, 10.4 knots. However, on 19 February, again in similar recorded conditions, the ship only maintained 9.5 knots and on 22 and 23 February, in similar conditions, she made 9.6 knots.

- In the light of those facts, it seemed to the tribunal right to conclude that in conditions which satisfied the requirements of the charter for the purposes of assessing performance, the ship could not do better than 10 knots. That was 1 knot short of the effective minimum warranty and on that basis the charterers’ claim was justified…

- See Lloyd’s Maritime Law Newsletter 826, London Arbitration 12/14 (2014) 900 LMLN 3.

- The Douglas scale has not been in general use on merchant ships since the Second World War. It is regarded by mariners and meteorologists alike as obsolete. Frequent references to Douglas in charterparties oblige arbitrators to determine what such references must be taken to mean. So, when a reference is made to Douglas sea state, a distinction has to be drawn between local sea state and swell. Douglas sea state 3 (DSS3), for example, must be taken as a reference to waves generated by local winds only and not to swell generated by weather conditions at a distance. Whether the parties (when entering into a charterparty) were aware of the distinction between the Douglas scale and Table 3700 or not is irrelevant, as they must be taken to have understood terms with an established meaning, even if their understanding is a misunderstanding.

- See Brian Williamson said in 《Understanding performance claims》 at p30.

- The two popular views generally expressed in London arbitration are:

- (a) ocean currents are a fact of life and should always be taken into consideration as a matter of course, and

- (b) if a warranty does not mention current, current-effect should be disregarded.

- Thus, consistency and logic dictate:

- (a) If a warranty makes no mention of current, it is to be assumed that

- the parties intended that no account is to be taken of currents.

- (b) If a warranty expressly excludes periods when adverse currents are

- encountered, those periods must be excluded.

- (c) If a warranty excludes adverse currents but makes no mention of

- favourable currents, no account can be taken of favourable currents.

- (d) Favourable currents should only be taken into consideration if that intention is clearly expressed in the wording of the warranty, otherwise they work to owners’ advantage.

- …That seemed consonant with the charterparty description of a “good weather” day, which specifically provided “no negative influence of swell”. Further, on the days in question, the general direction of the swell was either on, or forward of, the vessel’s port beam, that was to say, a negative influence on her passage through the water…

- See London Arbitration 12/14 (2014)900 LMLN 3

- The vessel’s speed maybe affected by current, and swell will cause the vessel’s pitching and rolling, which will reduce vessel’ speed.

- In the event, however, the point did not arise. The approach adopted by the tribunal in London Arbitration 15/07 was relevant to the language used in clause 29 of the subject charter. It was only adverse currents that were to be taken into account when considering whether the warranty was met or not; and periods of adverse current were to be excluded from the calculation of the vessel’s good weather performance. If the parties had wished to provide that the vessel’s performance was to be adjusted to reflect any positive influence of currents/swell they might easily have done so by providing for such an adjustment to be made in the clause itself. They did not do so: instead, they chose to refer only to any negative influence of currents/swell.

- See London Arbitration 21/18 (2018)1013 LMLN 1, where including “NO NEGATIVE INFLUENCE OF CURRENTS/SWELL”.

- Ocean currents were a fact of life and should be taken into account in the normal course of events. Where currents were adverse, a vessel’s performance should be credited. Where, as in the present case, the currents was positive, the vessel’s speed should be debited so as to arrive at the accurate assessment of her performance.

- See London Arbitration 15/05 (2005) LMLN 670 .

- Insofar as the charterers submitted that the warranty concerned the vessel itself and nothing else, that was not strictly correct. The warranty concerned the performance of the vessel in specified weather and sea conditions, including ones where there was a favourable current. The parties had agreed in clause 29 only to exclude adverse currents from consideration of the vessel’s performance without any mention of favourable ones. The owners were therefore correct in saying that the reference to the exclusion of periods of negative or adverse conditions was a concession to them: other periods, including ones of favourable current all formed part of the conditions in which the vessel’s performance was to be assessed for compliance with the warranty in clause 29.

- See London Arbitration 21/18 (2018)1013 LMLN 1.

- See London Arbitration 15/05 (2005) 670 LMLN 1:

- The House of Lords held that the route selected for a time-chartered vessel was a matter of employment and that the charterers were entitled to order the vessel to follow a particular route and the master was obliged to follow it in the absence of over-riding factors. The master remained responsible for matters of navigation and the safety of the vessel, her crew and cargo and if an order was given which, in the judgement of the master, exposed the vessel to danger or to a risk which the owners had not agreed to bear, the master was entitled to refuse it. The master remained responsible, however, to perform the voyage with the utmost despatch and otherwise to comply with the orders and directions of the charterers as to the employment of the vessel.

- So if no sufficient evidence, the master must follow the charterers’ weather bureau their recommendation.

- There was a fine distinction between a master's navigational responsibilities and his obligation as far as was reasonable to follow employment instructions. That was recognised by Lord Bingham in The Hill Harmony and by his Lordship's reliance on the words of Lord Porter in Reardon Smith Line Ltd v Black Sea and Baltic General Insurance Co Ltd [1939] Lloyd's Rep 64:

- “...It is the duty of a ship, at any rate when sailing upon an ocean voyage from one port to another, to take the usual route between those two ports. If no evidence be given, that route is presumed to be the direct geographical route, but it may be modified in many cases for navigational or other reasons, and evidence may always be given to show what the usual route is…”

- See London Arbitration 15/05 (2005) 670 LMLN 1

- Clause 122 allows a consistent discrepancy between the deck logs and independent source data to be referred to arbitration, so I can determine this issue. I have commented above about the absence of accurate weather recording equipment. Despite this, my preference is, where the entries in the deck logs show some but not necessarily total corroboration with independent source data, to adopt the observations made by the Master and ships’ officers on the spot, rather than analyses based on observations from space. However, in this case the weather reports from the vessel are such as to make it impossible to apply the speed warranty. I accept the Charterers contention that at the start of the northbound leg the vessel must have encountered calmer conditions falling within the qualifications contained in clauses 29 and 122 than those that were reported by the vessel. I will therefore adopt their approach based on independent source data.

- See The “Evnia” case.

- It is therefore not strictly necessary for me to express a view as to which of the three interpretations is to be preferred. However, it seems to me for the reasons that I have already indicated the last paragraph of cl. 26 explains the effect to be given to particulars about the vessel in the paragraph which are qualified by the word "about". This interpretation gives effect to the last paragraph of the clause, and also gives it a narrow effect that meets the concerns expressed by Lord Roskill, and cannot, in my view, be said to be uncommercial. I am aware that I should be cautious of interpreting the last paragraph of the clause as providing that "about" has been given a meaning which is not the ordinary meaning. However it is no part of my preferred interpretation that the word about is stripped of its usual meaning of affording a margin to the stipulated figures. The qualification at the end of the paragraph is to be interpreted as adding a further stipulation, that the "about" estimations have the status only of bona fide representations.

- I therefore conclude that answer to the point of law raised on this appeal is that the charter-party does not contain a warranty about the vessel's rate of fuel consumption.

- See The “Lipa” [2001] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.17

- Nothing was said in clause 29 about weather or sea conditions. The charterers said that that meant that the owners warranted that the ship would perform under the charter at the stated speed and consumption, whatever the weather. The owners said that, on the contrary, the warranties only applied in perfect conditions, and that since between Alge_iras and the Brazilian discharge port the ship performed at 12.09 knots, ie “about” 12.50 knots, there was no breach.

- Held, that the tribunal did not accept the owners' argument. In the tribunal's experience it was very unusual to find such an unqualified warranty in a normal charter. Nevertheless, the tribunal did not see how it could fairly read the relevant words in clause 29 as the owners suggested. The natural meaning of the words was that the ship was to perform at the stated speed and consumption throughout the trip. If the owners had wanted to qualify their obligations in some way, they should have inserted words such as the common “in good weather and smooth water”, or even “without guarantee”. Otherwise the words had to given the broad meaning argued for by the charterers.

- See London Arbitration (2006)LMLN 682

- As the charterers had pointed out, on the owners’ case there would be a saving of bunkers to be set off against time lost if the vessel merely maintained its warranted consumption of 46 mts of IFO per day. There was no legal or commercial sense in such a conclusion. The margin permitted by the term “about” was clearly intended to act as a shield against claims that would otherwise be made against the owners rather than as a sword to cut down the measure of the charterers’ other losses. The owners could not be heard to say that “the vessel underperformed and consumed more bunkers than described but because it did not overconsume as much as it might have done we can treat that as a saving and reduce your loss of time claim”. For that reason the tribunal would reject the owners’ submission that any saving in bunker consumption should be measured by reference to its warranted consumption plus 5%.

- See London Arbitration 20/7 (2007) 723 LMLN 3.

- I agree with the Charterers that when the expression “good weather” appears in isolation, it is normally taken to mean up to and including Beaufort Wind Scale force 4 and Douglas Sea State 3. It is, however, open to the parties to a charter to explicitly state how good weather is to be defined in the contract, either confirming or altering the conventional interpretation.

- In the present case, on an objective reading of the words used in the speed and consumption clause, I conclude that the parties intended to modify the conventional definition so that Beaufort force 4 and Douglas Sea State 3 were not to be considered good weather. The presence of the word “under” must be taken into account and I can see no other way of construing this clause than to accept that good weather in this instance is to be defined as up to and including Beaufort 3 and Sea Scale 2.

- Comments from Arbitrator for unreported case, capesize vessel.

- See The “Didymi”[1988] 2 Llody’s Rep.108 (C.A.) case,Clause 30 where provides:

- (4) Similarly if it is found that the vessel has maintained as an average…a better speed and/or consumption…owners shall be indemnified by way of increase of hire, such increase to be calculated in the same way as the reduction provided in the preceding sentence…

- -Held, by C.A. (Dillon, Nourse and Bingham, L.JJ.), that (1) the provision in issue related to a subsidiary and non-essential question of how a contractual liability to make payment according to a specified objective standard was to be quantified; the substantial provision in sub-cl. (4) was that the "Owners shall be indemnified by way of increase of hire such increase to be calculated"; the procedure for calculation was a matter of machinery and there was a binding obligation to which effect could be given as a matter of contract.

- First, assess the vessel's performance in good conditions as defined on all sea passages from seabuoy to seabuoy, excluding altogether any period of slow steaming at the charterers' request;

- Secondly, if a variation of speed from the stipulated norm is shown, that variation should be applied with the necessary adjustments and extrapolations to all sea passages from seabuoy to seabuoy in all weather conditions, but excluding periods of slow steaming at the charterers' request;

- Thirdly, if there is a variation of consumption from the stipulated norm, that variation should be applied, with the necessary adjustments and extrapolations, to all sea passages from seabuoy to seabuoy in all weather conditions, including periods of slow steaming at the charterers' request.

- See The “Didymi” [1988] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.108 (C.A.) per Nourse, L.J.at p117.

- It is common ground that sub-cl.(4) provides what the Judge called a contractual yardstick for measuring the extent of the vessel's capacity to perform. That being so I can see no reason for confining the application of the yardstick to the periods when the weather was force 4 or less. The warranty set out in sub-cl.(1)-(3) is expressed to apply generally in respect of all sea passages whether laden or in ballast. Prima facie the charterers are entitled to be compensated for any breach of that warranty. A vessel which cannot comply with her contract speed or consumption in good weather, is unlikely to be able to comply with the contract when the weather is bad. I would therefore expect sub-cl.(4) and (5) to provide the machinery for assessing compensation for any breach of warranty in respect of the weather. I can think of no sensible business reason why the parties should have intended charterers to be compensated for under-performance in periods of good weather, but not in periods of bad weather.

- See The “Gas Enterprise” [1993] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.352 (C.A.) per Lloyd, L.J.at p365.

- The conclusion that I have reached, with some hesitation, is that the charterers' interpretation of revised cl. 5 is to be preferred. If the owners had intended to warrant the ship's performance only in good weather conditions,then they could and should have stated that expressly or at the very least included in clear language among the periods to be disregarded when making calculations under sub-cl. (4) those periods when the weather conditions were above force 4 on the Beaufort Scale. In my judgment, the words "up to and including Beaufort Force 4 wind and wave" qualify the conditions in which distance made, time taken and quantity of bunkers consumed by the vessel are to be ascertained and measured against the table in sub-cl. (3) and do not qualify the words "the passages as actually carried out by the vessel" so as to confine the operation of sub-cl. (5) to those parts of the passage when the weather conditions were force 4 on the Beaufort Scale or below.

- See The “Gas Enterprise” [1993] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.352 (C.A.) per Roch, L.J.at p368-369.

二十七、Calculation methods

二十八、Assessment of the breach

- Weathernews’ ship performance assessment methodology is in compliance with English case law, a Good Weather Analysis method, as set out in London law precedents such as by The Didymi [1987] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.166 and The Gas Enterprise [1993] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 352.

- It is clear from these authorities that speed and consumption are to be evaluated by reference to performance in good weather; once the extent of under-performance is established, in accordance with warranty conditions, any discrepancy should then be applied throughout all periods even when warranty conditions do not exist.

- The objective of the voyage analysis is to establish good weather periods when warranty conditions exist, both independently and cumulatively, in order to permit an evaluation of the ship’s capability, in terms of speed and consumption, to establish whether the warranty had been met. Where there has been a breach, it is appropriate to establish the extent of the breach in order to determine how charterers are to be compensated.

- Whatever assumptions experts make in their evaluation of a ship’s performance, they should be clearly stated. An expert will not be criticised for setting out in clear terms the parameters he has adopted in a voyage analysis, indeed that is a welcome approach. Calculations, using a range of allowances, are an acknowledgement that final determination of appropriate allowances is a matter for the tribunal.

- If deck logbooks are used as the source of weather data, this should be clearly stated in the expert’s report. If there appears to be a consistent discrepancy between the weather recorded in the deck log and weather data used by a routing company, an acknowledgement of the fact will manifest the expert’s independence. It is however a matter for the expert’s instructing solicitors whether any further evaluation, using the weather data provided by a routing company, should also be carried out.

- Whatever assumptions experts make in their evaluation of a ship’s performance, they should be clearly stated. An expert will not be criticised for setting out in clear terms the parameters he has adopted in a voyage analysis, indeed that is a welcome approach. Calculations, using a range of allowances, are an acknowledgement that final determination of appropriate allowances is a matter for the tribunal.

- If deck logbooks are used as the source of weather data, this should be clearly stated in the expert’s report. If there appears to be a consistent discrepancy between the weather recorded in the deck log and weather data used by a routing company, an acknowledgement of the fact will manifest the expert’s independence. It is however a matter for the expert’s instructing solicitors whether any further evaluation, using the weather data provided by a routing company, should also be carried out.

- A contract must be construed as a whole, read all provisions/clauses together.

- Speed and consumption clause, eg:

- Speed and consumption basis good weather day (day means continuously 24 hours from noon to noon) of under Beaufort force 4 and Douglas sea state 3 (means significant wave height less than 1.25 M) and no adverse current and no negative influence of swell with clean hull on about 12(L)/13 (B) knots on about 33mt(L)/32mt(B) per day +0.1mt MDO, about means tolerance of 5%. The figures were given in good faith and for reference only .

- Speed and consumption basis good weather condition of upto Beaufort force 4 and Douglas sea state 3 on 12(L)/13 (B) knots on 33mt(L)/32mt(B) per day +0.1mt MDO, which should be applied to all voyages .

- Which one was better? Depend on your position, charterers or owners.

- The natural construction which, in any event, should be put upon those particular words, each condition must be took into consideration.

海运圈聚焦专栏作者 Alex (微信公众号 航运佬)

2018-12-13

2018-12-13 2176

2176